Site Navigation Menu

The midcoast was inhabited for thousands of years before the Europeans arrived. Bruce Bourque’s Twelve Thousand Years: American Indians in Maine gives an overview of Maine’s “prehistory” as well as an introduction to Maine’s written history. The Europeans arrived during, and contributed to, a period of intense transition for the native Mainers. Bourque says [p. 107], “It is often difficult to identify the ethnicity of specific groups . . . the region was undergoing two separate transitions by the time the Europeans began to write descriptions of people. The two transitions that were affecting the region at the time of contact were the movement eastward of the maize-based horticulture [represented by the Abenaki of Norridgewock] and the influence of the European traders.” In general, the people who were here in Camden were called Penobscots. Sometimes the term Tarrantines is used, which more often referred to the eastern Maine tribe, the Micmacs, as well as Penobscots, Passamaquoddies, and Maliseets. There is surprisingly little detail in the local history on our original inhabitants. One historian (Kerry Hardy, Notes on a Lost Flute: A Field Guide to the Wabanaki) says that the great battle in which the Abenaki leader, or Bashaba, was killed by the Tarrantines (Tarratines, Tarrentines) in 1615 may have taken place at the foot of Mt. Battie. There are conflicting descriptions whether the Penobscots were part of the Tarrantines, or allied with the Abenaki.

In 1605, Captain George Weymouth of the ship Archangel first sighted the Camden Hills on his voyage to midcoast Maine. He sailed up Penobscot Bay and anchored on June 12, 1605 not far from the land “abreast the mountains since called Penobscot Hills” (Camden Hills). In 1614, Captain John Smith described the Camden Hills thusly — “the high mountains of Penobscot, against whose feet doth beat the sea.” However, it was not until 1769 that the first settlers arrived following the completion of a survey of the Waldo Patent by the Twenty Associates in 1768. The survey named the area now known as Camden and Rockport as part of the Megunticook Plantation, from an Indian name meaning “great sea swells.” In 1769 James Richards, the first settler, built his log cabin, but it was not until after the American Revolution in 1791 that the town was named for Charles Pratt, first Earl of Camden. Pratt was a judge and nobleman who sympathized with the colonists during the Revolution.

During Camden’s first hundred year s the town had a steady growth in population and a prosperous economy. The 1870 census recorded a population of 4512 and a valuation of $1,497,631. Numerous industries supported the population including shipbuilding, an anchor factory and the lime industry. The latter was located in what today is known as Rockport but was then called Goose River.

s the town had a steady growth in population and a prosperous economy. The 1870 census recorded a population of 4512 and a valuation of $1,497,631. Numerous industries supported the population including shipbuilding, an anchor factory and the lime industry. The latter was located in what today is known as Rockport but was then called Goose River.

Goose River separated from Camden in 1891 and became the town of Rockport. This separation not only deprived Camden of three-quarters of the town’s territory and half of the population but also the profitable lime and ice harvesting industries.

ice harvesting industries.

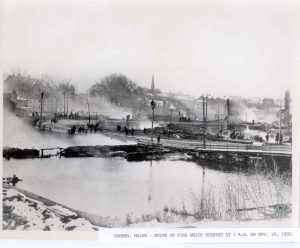

In 1892 a fire destroyed nearly all of Camden’s business district. However, Camden citizens quickly rebuilt the downtown area using brick instead of wood, thus leaving a legacy of permanence and grace that exists to this day.

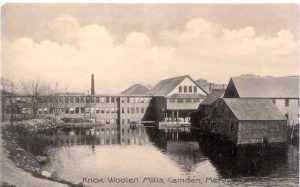

As the 19th century came to an end, Camden was very much a shipbuilding town with the H.M. Bean Yard launching the largest four-masted schooner and the first six-master ever built-the George W. Wells. Several woolen mills along the Megunticook River prospered well into the 20th century. The Knox Woolen Company. made the world’s first endless paper-making felt and was Camden’s largest employer.

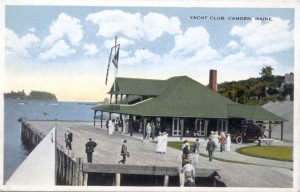

The turn of the century brought a new era to Camden as its natural beauty began to attract some of the wealthiest families in the country. These families built large summer “cottages” to rival those in Bar Harbor. Families such as Curtis, Bok, Keep, Gribbel, Dillingham and Borland not only built beautiful estates but their generosity to the community resulted in the elegant public library and Amphitheatre, Harbor Park, the Village Green, the Camden Yacht Club  and the Camden Opera House. Magnificent private yachts such as Cyrus Curtis’ Lyndonia filled the harbor.

and the Camden Opera House. Magnificent private yachts such as Cyrus Curtis’ Lyndonia filled the harbor. Yachting continued throughout the 20th century with the unique HAJ Boat racing fleet at the Yacht Club with the younger sailors in their turnabouts. In the 1940’s the cruise schooner business was started by Captain Frank Swift and the windjammer fleet continues to this day.

Yachting continued throughout the 20th century with the unique HAJ Boat racing fleet at the Yacht Club with the younger sailors in their turnabouts. In the 1940’s the cruise schooner business was started by Captain Frank Swift and the windjammer fleet continues to this day.

Music and cultural interests flourished with the establishment of the internationally renowned Summer Harp Colony founded by Carlos Salzedo and the founding of Bay Chamber Concerts. Theatre productions at the Opera House and Shakespeare in the Amphitheatre enriched the lives of residents and summer visitors. Edna St. Vincent Millay, who grew up in Camden, achieved world-wide recognition for her poetry and won the Pulitzer Prize. The movies came to Camden in 1957 when the controversial film, Peyton Place, was filmed here. Hollywood used the Camden area for the locale of many more movies in later years.

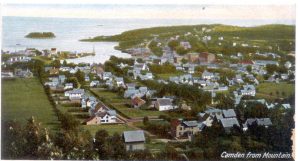

Throughout the 20th century Camden became both a resort town and a retirement community. Because of its natural beauty-mountains, lakes and ocean,– many summer visitors came to enjoy this area. In 1965 a road was built up to the top of Mt. Battie through the Camden Hills State Park enabling thousands of people to enjoy an expansive view of Penobscot Bay as well as Megunticook Lake.

During the last half of the 20th century, Camden’s economy thrived due to the tourist industry, electronics industry, tannery, woolen mills and boat yards. In the 1990’s, MBNA, one of the nation’s largest credit card companies moved into the former Knox Woolen Mill buildings. Not only were the buildings beautifully restored but hundreds of jobs were available to the young people of the area.

As Camden entered the 21st century, it has succeeded in preserving its natural beauty, has a strong economy, provides diverse educational and cultural opportunities and fosters a strong sense of community for its residents.

Once located in the township of Camden, which extended from Clam Cove to Ducktrap River and ten miles inland, Rockport, or “the River”, was settled in 1769 by Robert Thorndike. Rockport’s first settler obtained land from the Twenty Associates and built a small cabin near the mouth of the harbor.

Eighteen dwellings dotted the shores of Goose River Village. The sole industry was the salt works, on Beauchamp Point, owned by General Estabrook. The “Granite Block” (the present Corner Shop) housed a general store and post office.

William Carleton moved his business ventures from Camden (“the Harbor”) to Rockport. This brought shipbuilding, lime burning, and ice exporting to the Goose River.

As Rockport’s first vessel, the 104-ton Lucy Blake, was sailing out of the harbor, the keel was being laid for the Tennessee, the first full-rigged ship at Eells Shipyard.

Under the Carleton Norwood shipyard flag, numerous vessels were constructed, including the largest square-rigger ever built and launched on Penobscot Bay, the Frederick Billings.

In this year, the good citizens of Goose River voted to officially change the name of the village to Rockport.

Lime was king, and Rockport was one of the greatest lime-producing towns in America. Lime was quarried in the village area and in Simonton’s Corner.

The Joe Shepard, a narrow-gauge railroad, transported lime from the Corner to Rockport Village. The kilns burned night and day, 365 days a year.

The Lily Pond annual harvest of 50,000 tons of ice was shipped worldwide. Rockport Ice Company was known for its famous “Lily Pond Ice”, which was so clear that one could read the New York Times through a cake of ice.

The “Bridge Question” divided the towns of Camden and Rockport, and each town became a separate entity.

The Camden-Rockport Street Railway added track to the existing Rockland Street Railway and built a power-house in Clam Cove.

A fire starting in the lime sheds spread across the harbor to the ice houses and became the straw that broke the back of industry in Rockport. Neither industry was ever rebuilt, and the business decline of Rockport began.

During the height of its economic success, Rockport’s business block rivaled those of larger cities and included the first bank in the area.

The Megunticook Golf Club was established as the area’s first golf course and remains today a private golf club.

Central Maine Power Company purchased the RTC Street Railroad and constructed the first amusement park in the area, known as Oakland Park.

Mary Louise Curtis established the Curtis Institute of Music Summer Colony. Musicians came from all over the world to study with renowned artists. Concerts were held in the Eells Boat Barn.

Rockport High School’s Seaside Wonderland Carnival was held at Rockport Harbor.

Rockport’s first park, Walker Park, was built on lime deposits and named for Selectman Arthur Walker.

Maine Coast Artists was established by local artists and then renamed the Center for Maine Contemporary Art in 1999.

Aldermere Farm, owned and operated by Albert Chatfield, imported Belted Galloway cattle to Rockport.

Camden and Rockport school systems consolidated to form Maine School Admistrative District 28.

Andre the Seal became a Rockport celebrity.

Penobscot Medical Center, a 109-bed, full-service hospital, opened in Glen Cove.

Maine Photographic Workshop offered its first workshops and achieved status as Rockport College in 1996.

Lime Kiln Preservation Park was established at Rockport Harbor.

Bay Chamber Concert Series relocated to the Rockport Opera House.

Mary Lea Park was constructed in honor of Mary Louise Curtis Bok and Lea Luboshutz.

Cramer Park was dedicated to Mary Meeker Cramer and Ambrose Cramer for their tireless efforts in preserving local history.

The Rockport Garden Club sponsored a million-dollar restoration of the Rockport Opera House.

Today, Rockport is a community of 3,209 residents who enjoy the ambience of living and working in a village that fosters the arts, industry, and ties to the historic past.

Lincolnville’s earliest inhabitants were probably “summer folks”, Native Americans who traveled down to the coast to camp along the shore, fish and dig clams. Their middens, or garbage dumps, provide tantalizing clues to their way of life, not only what they ate, but the kind of pottery they made and the stone and bone tools they used. If something got broken it ended up in the midden along with thousands of clam shells and animal bones. In the fall it’s believed these people returned to the inland forests for the winter.

Early European explorers sailed right by Lincolnville’s four miles of shoreline, and although undoubtedly some landed and looked around, they left no trace or record. The late 18th century saw some settlement along the coast, but none are recorded until 1770 when Nathan and Lucinda Knight tramped inland to the head of the marsh meadow that occupies the middle of the town. The couple built a log cabin near a stream east of today’s Center and stayed, earning the title of First Settlers. With the end of the Revolutionary War families from southern New England streamed into Maine in search of free land. Some of them settled in Lincolnville, which by then was divided into two “plantations”, Canaan and Ducktrap. The free land turned out to come with a price, for it was actually part of the Waldo Patent, and claimed by Gen. Henry Knox of Thomaston as part of his wife’s inheritance. For the next several years, Knox’s agents were besieged by irate settlers when it came time to pay up. His man at Ducktrap was George Ulmer, who had been granted by Knox the mill rights to the Ducktrap stream. On two occasions Ulmer awoke to find his logs adrift in the Bay; angry residents had, in the night, cut the cable holding them in the Trap.

By about 1800 the two plantations were “settled”, meaning the people had paid Knox, and in 1802 they were joined into one town, incorporating as Lincolnville, named for General Benjamin Lincoln. For the next half century, the town grew vigorously to a population of 2,154 in 1850. Lumbering, lime burning, ship building, and farming occupied the people. In the 1840s Lincolnville shipped 400,000 casks of lime a year, rivaling Rockland and Rockport. Brigs full of wheat sailed from the Beach, and large ships were built at shipyards at both Ducktrap and the Beach. If a man wasn’t a farmer, he was probably a sailor, and many were both.

The Civil War reversed the growth trend, however, and after that war Lincolnville began to lose population steadily. In spite of that Ducktrap thrived as a little industrial community with a large patent lime kiln fed with a horse-drawn railroad that carried the lime rock from an inland quarry. A busy sawmill and grist mill, cooper shops, stores and a school completed the scene there. By 1905, though, all these enterprises had closed; more and more young people left town and the state to find work. Tending to summer people became a seasonal job for many. They worked as caretakers, laundrywomen, drivers, and cooks. Farmers took to peddling their products to Lincolnville’s summer population as well as in Camden and Belfast.

By 1920 only 811 people were counted in the census. Most of these were farmers, at least part of the time. Jobs in Camden’s mills occupied many. Others signed up for the First World War. During the Depression families used to living off the land were able to survive quite well. But following the Second World War farming as a way to make a living was pretty much over for all but a few hardy farm families. The Beach saw motor courts and cabins spring up for the automobile tourist; restaurants made up the core of the Beach’s economy (and still do). Today’s population has finally surpassed the high of 1850 as Lincolnville has become a popular retirement town, as well as the good place to raise a family it has always been.